Care Against Growth

Sidewalk Labs’ smart city project in Quayside, Toronto has become a combination of technological lodestar and discursive black hole. Since Sidewalk’s initial response to Waterfront Toronto’s Request for Proposals in 2017 to develop the Toronto waterfront, up through the recent release of the Master Innovation and Development Plan earlier this year, every tortured step in the process has been under justly deserved scrutiny. Of these, Bianca Wylie’s excoriation of the project’s governance nightmares,1 Shannon Mattern’s deflating of Sidewalk’s community engagement and attempts at ‘co-design’,2 and Molly Sauter’s discussion of the colonial eye of the project’s renderings are all indispensible.3 My focus today is much smaller in scope—about a meter in diameter, if memory serves.

In Quayside, despite pretenses to universality, the details betray the whole. This hexagonal modular paver is a microcosm of the preoccupations of the entire project. Visitors to Sidewalk Labs’ 307 in Toronto can see this unassuming piece of infrastructure rendered in work-in-progress plywood, developed in partnership with Carlo Ratti Associati of Senseable City fame. Like many of 307’s installations, the intention is to get visitors ‘familiar with the future’, in which the paver becomes a cell in a system called ‘Dynamic Street’.4 The Dynamic Street is intended to fulfill Sidewalk’s promise from the 2017 RFP that Quayside will be a place “where the only vehicles are shared and self-driving…[and] where streets are never dug up”.5 Further, beneath the Dynamic Street open access utility channels in the roadbed will “work as a pair to increase the ease of utility work”.6 That assurance of undisrupted service has a higher goal as well—that the urban fabric itself will be enabled to “evolve as technology changes”7 and, ultimately, to “create a streetscape that responds to citizens’ ever-changing needs”.8 307 visitors are given a “digital reconfigurator” enabling them “design urban scenarios of their own”,9 “in order to swiftly change the function of the road without creating disruptions on the street”.10 To this end, Dynamic Street proposes the entire hardscape be turned into a fluid chessboard, dispensing with curbs in favor of a gradient to be defined by changing color lights, maintained by sensor suites, and given structure solely via ad hoc parking enforcement and digital signage, all of which plug directly into the paver as needed.11 And if that wasn’t enough, these pavers will also have heating coils to melt snow.

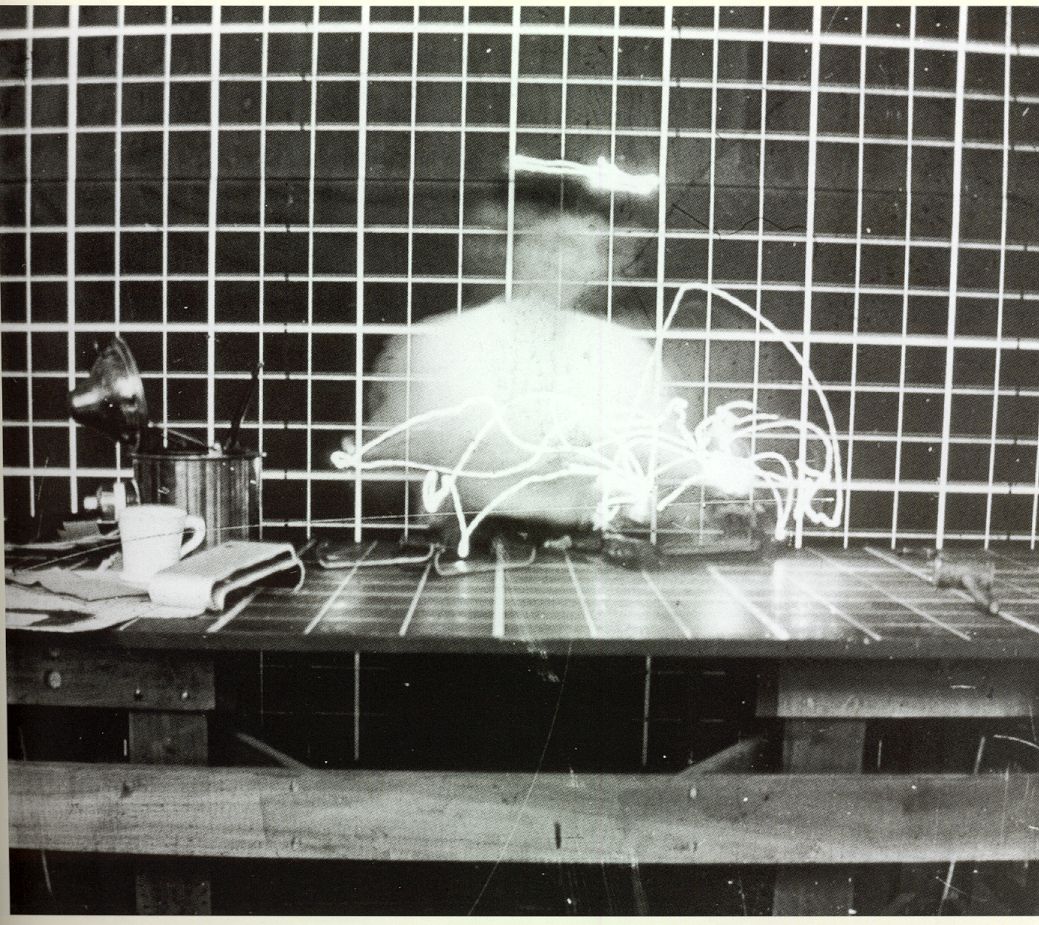

But before any of that can happen, it’s helpful to look briefly at the provenance of this miracle chunk of concrete. In 2012, the paver concept began in the research labs of the French Institute of Science and Technology for Transport, Development and Networks, or IFSTTAR. Back then, it was called the “Removable Urban Pavement” (or RUP). According to IFSTTAR, the RUP was intended to allow a street to be “opened and closed within just a few hours using very lightweight site equipment, in restoring the initial street appearance and all its functionalities”.12 It was tested in the field in two French cities (Nantes and Saint-Aubin) and eventually abandoned.

There is a significant difference between the IFSTTAR RUP and Sidewalk’s Dynamic Street—not so much in the childlike, kitchen sink addition of technological capacity but in the paver’s recontextualization as a system which encompasses mobility, spatiality, governance, and so on. From the relatively small figure of the paver comes a landslide of repercussions. Imbricated is Sidewalk’s own dim view of urbanity, in which the city is a device for liquidating of any and all solid ground in favor of technological purity. The Dynamic Street, while seemingly the more innocuous of Sidewalk’s many proposed innovations, already contains the germ of not just its technological but its political goals. They even admit as such: “Sidewalk Labs recognizes that this new approach to street systems would require changes to existing regulations and operations,” the MIDP confesses.13 This move is Sidewalk’s forte: proposing an urban ‘innovation’ which, to enact, would require ‘minor’ restructuring of the state, a little transfer of power, no big deal. In this case, Sidewalk will likely argue for an exemption from the City of Toronto’s typical 20- or 30-year roadbed maintenance cycles. If the MIDP is accepted and the project goes forward, they will almost certainly get it.

Another forte of Sidewalk’s is their laughable ineptitude (or, more cynically, lack of concern) with the physical realities of their proposals. Case in point: in a video released by Sidewalk, each individual module is shown to interconnect with others for stability.14 IFSSTAR field tests using a similar design found local single-paver replacement impossible with this interlocking “connection key” design, instead requiring all modules within a 120 degree dihedral to be removed for access.15 Compare this to Sidewalk’s twee graphic, which shows a single worker using a machine to remove a single paver. There is no elaboration on Sidewalk’s part as to the eventual realities of this system.

Within this technical failure is the core of the wider technocratic attitude to lived reality as something by nature disposable. The machine-aided worker picking over the city and hot-swapping out parts of the street is an argument about labor as an urban practice, or specifically, against labor. When we see this intrepid figure, faceless, appearing just in time, we are shown labor as an automatic reproductive process of the city itself. Maintenance-labor is displayed as a background process, the mindless swapping of self-identical parts performed by self-identical workers. It is merely a logistical issue, undertaken by a labor pool, by workers ‘in general’. This is not new. Marx notes that capital does not consider the worker, when not working, as a human being—but it doesn’t consider them as very human while working either.16 Concomitant with the organization of labor, capital seeks to make labor invisible. This invisibility, or the removal of humanity, of people who work, allows capital to perpetuate an idea that its growth is infinite. Thus the city can presented as a holisticism, an organic Thing which grows and adapts on its own to “the emergence of [the] new”17 and pursuing relentless “optimization” towards a climax state.18 This city-organism-machine, as an intensification and spatialization of already-logistical capital, has its origin in the dehumanization and concealment of labor. This isn’t automation but being made to work as an automaton. “To work today is to be asked,” Fred Moten and Stefano Harney write, “…to do without thinking, to feel without emotion, to move without friction, to adapt without question, to translate without pause, to desire without purpose, to connect without interruption”.19 If the work can’t be done by computers, workers must become computers, swarming like von Neumann machines.

From this perspective, Sidewalk’s blasé attitude towards the materiality of Quayside starts to make sense: it’s only a crude means to the delirious end of total logistics. Only a minimum armature is needed for the maximal extension of logistics into the sphere of everyday life.20

But there is a certain aspect of labor, unquantifiable by capital, which can be used as a weapon against our logisticization—the consideration of labor as a social relationship with our selves and our world, in which work is not toil for a wage, but an expression of care. The most acute representation of labor-as-care is probably found in unpaid, usually domestic, labor. Maria Puig de la Bellacasa describes care as a social activity, “a signifier of devalued ordinary labours that are crucial for getting us through the day”.21 Monique Lanoix explains this caring work is a litany of “embodied practices” and notes it is undertaken predominantly by women and people of color.22 But care, without diminishing the necessity and crucially denigrated role of unwaged work under capitalism, is present in both production and reproduction. More generally, it is the ‘personal reason’ to the question “why are you doing that?”. Care, as an unvalued and invaluable sociality which can be present in work, digs deep below both the capitalist wage relation and the division of labor, founding a universality that underpins various labors and engenders an understanding of work as a social practice which can and does exist apart from capital.23 Capital thus seeks to make care impossible; the divisions get deeper and the wages more extractive, in which capital, on some level, becomes what Lucy Suchman calls “a sociotechnical assemblage [which] can reinforce asymmetrical relations that devalue caring”.24 Value is presented as the only thing that matters. Achille Mbembe warns that “[u]nless we reinvent the terms of what counts and in the process resignify what value stands for as well as the procedures of assigning value, of measuring value, of exchanging value, things won’t change”.25

Sidewalk Toronto’s thirst for absolute technological growth is a fanatical headlong rush to maximalize value. It and care are mutually exclusive. Care cannot be bought, it does not respond to logistics. But first we must recover it. Care not only means that the designer, programmer, street sweeper, carpenter, bus driver, and custodian all share an economic identity, but that this economic identity imposed by capitalism also contains the burning core of a new social formation. Hypersequestration in the division of labor breeds hierarchicalization of disciplines, while at the same time obscuring the ‘big picture’, pushing care away until it slips through the cracks. “In capitalist usage, not just machines, but also ‘methods’, organizational techniques, etc., are incorporated into capital and confront the workers as capital: as an extraneous ‘rationality’”, a “sociotechnical assemblage”.26 This assemblage produces progress, rationality, inevitability. It is the enemy of care.

“[W]e could imagine physical infrastructures that support ecologies of care — cities and buildings that provide the appropriate physical settings and resources for street sweepers and sanitation workers, teachers and social workers, therapists and outreach agents,” Shannon Mattern writes.27 If given the possibility, work which is consciousness of itself as a social expression of care would necessarily create these infrastructures to sustain it. But this won’t just happen: we need new theoretical standpoints. For example, we can enact a radical inversion of capitalism’s history, which turns away from capitalism’s own mythologization of infinite growth and instead recognizes capital as lead by labor.28 The effects of this inversion are immense: we can see ourselves as creating our world—currently a landscape of violence, exclusion, brutality, and yes, technological splendor—and begin to wonder why we have been tasked with building our own hell. This question is immediately followed by another: how can we stop, and regain control of ourselves, our work, our world? The answer to this question is by exploring and enacting care as a social and material approach to everyday life.

This new standpoint throws the differences between the RUP and the Dynamic Street into harsh relief. Though IFSTTAR is by no means a hero of the world to come, the RUP process offers an instructive example of what care could look like in an infrastructural context. In the RUP report, I was shocked to find that the pavers themselves were ultimately not the essential element, though that was the initial intention of the project. After design meetings with engineers and “network operators”, the RUP team realized that the paver itself was less important than the substrate beneath it, and returned to the drawing board. Engineers developed a new substrate, which they called “Structural Excavatable Cement-Treated Material” (or SECTM). IFSTTAR’s report recognizes SECTM as the “most innovative aspect” of the project, overall facilitating the RUP’s promise for greater ease of maintenance and installation.29 When Sidewalk and Carlo Ratti Associati adapted the RUP for Toronto, they conspicuously left out SECTM. Even small, seemingly economical designs and dialogues such as this one can potentially become the way we build our world: not as a concatenation of technologies and immutable concepts, but as close collaboration, as the expression of social relationships, as care. Putting this into practice currently puts us at war with the inexorable rise of technological urbanism like Sidewalk’s—a war which we may be already losing.

Notes

-

Wylie’s Medium page is an inexhaustible and incredibly valuable repository of information about the Sidewalk Toronto process as well as full of brilliant ruminations on the threats it poses to governance, privacy, and citizenship. See more at Bianca Wylie, “Collected Medium Posts,” Medium, accessed September 19, 2019, https://medium.com/@biancawylie. ↩

-

Shannon Mattern, “Sidewalk Labs’s Material Co-Design,” Words In Space (blog), April 28, 2019, http://wordsinspace.net/shannon/2019/04/28/sidewalk-labss-material-co-design/. See also Shannon’s now-canonical “The City is Not a Computer” and “Instrumental City”, both at Places Journal. ↩

-

Molly Sauter, “City Planning Heaven Sent,” e-flux Architecture, February 1, 2019, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/becoming-digital/248075/city-planning-heaven-sent/. ↩

-

Rima Sabina Aouf, “Carlo Ratti and Sidewalk Labs Collaborate to Build Reconfigurable Dynamic Street,” Dezeen, July 20, 2018, https://www.dezeen.com/2018/07/20/the-dynamic-street-reconfigureable-paving-system-sidewalk-labs-carlo-ratti-associati/. ↩

-

Sidewalk Labs, “Request for Proposals: Innovation and Funding Partner for the Quayside Development Opportunity,” October 17, 2017, 17, https://sidewalktoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Sidewalk-Labs-Vision-Sections-of-RFP-Submission.pdf. ↩

-

Sidewalk Labs, “The Urban Innovations,” Draft Master Innovation and Development Plan, June 24, 2019, https://www.sidewalktoronto.ca/midp/, 136. ↩

-

Sidewalk Labs, “MIDP,” 137. ↩

-

Aouf, “Carlo Ratti and Sidewalk Labs Collaborate to Build Reconfigurable Dynamic Street.” ↩

-

Carlo Ratti Associati, “The Dynamic Street,” Carlo Ratti Associati, 2018, https://carloratti.com/project/the-dynamic-street/. ↩

-

“Dynamic Street for Sidewalk Labs,” Smart Cities World, accessed September 19, 2019, https://www.smartcitiesworld.net/news/news/dynamic-street-for-sidewalk-labs-3152. ↩

-

Sidewalk Labs, “Sidewalk Labs Street Design Principles,” Sidewalk Labs Street Design Principles, accessed May 12, 2019, https://sidewalklabs.com/streetdesign. ↩

-

François de Lerrard, Thierry Sadran, and Jean Maurice Balay, “Removable Urban Pavements: An Innovative, Sustainable Technology,” The International Journal of Pavement Engineering 31p (2012): 1–2, https://doi.org/hal-00850769. ↩

-

Sidewalk Labs, “MIDP,” 135. ↩

-

“Sidewalk Toronto on Twitter: ‘Our Hexagonal Street Paving System at 📍#307LSBE Will Be Ready for Open Sidewalk: Winter Warmer on March 2nd. Permeability, Heating, LED Lighting, and Modularity Enable the Pavers to Adapt to Community Needs and Minimize Disruptions. Https://T.Co/YccWAIXuRM’ / Twitter,” Twitter, accessed September 18, 2019, https://twitter.com/sidewalktoronto/status/1100036913103290368. ↩

-

François de Lerrard, Thierry Sadran, and Jean Maurice Balay, “Removable Urban Pavements: An Innovative, Sustainable Technology,” 24. See especially Figure 12. ↩

-

Buret quoted in Karl Marx, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, trans. Martin Milligan (Amherst: Prometheus, 1988), 50. ↩

-

Sidewalk Labs, “MIDP,” 138. ↩

-

Sidewalk Labs, “Sidewalk Labs Street Design Principles.” ↩

-

Fred Moten and Stefano Harvey, “Fantasy in the Hold,” in The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Brooklyn: Minor Compositions Press, 2016), 87. ↩

-

Panzieri, Raniero. “The Capitalist Use of Machinery: Marx versus the ‘Objectivists.’” In Outlines of a Critique of Technology, edited by Phil Slater. Ink Links, 1980. ↩

-

Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, “Matters of Care in Technoscience: Assembling Neglected Things:,” Social Studies of Science, December 7, 2010, 94, https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312710380301. ↩

-

Monique Lanoix, “Labor as Embodied Practice: The Lessons of Care Work,” Hypatia 28, no. 1 (2013): 85–100. ↩

-

Bruno Gulli, Labor of Fire: The Ontology of Labor between Economy and Culture (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2005). ↩

-

Bellacasa, “Matters of Care in Technoscience,” 97. ↩

-

Sindre Bangstad et al., “Thoughts on the Planetary: An Interview with Achille Mbembe,” New Frame, September 5, 2019, https://www.newframe.com/thoughts-on-the-planetary-an-interview-with-achille-mbembe/. ↩

-

Panzieri, Raniero. “The Capitalist Use of Machinery: Marx versus the ‘Objectivists.’” In Outlines of a Critique of Technology, edited by Phil Slater. Ink Links, 1980. ↩

-

This inversion is discussed more fully in Mario Tronti, “A New Type of Political Experiment: Lenin in England,” in Workers and Capital, trans. David Broder (Verso, 2019). More generally, it occupies a central theoretical obsession of operaia, particularly the editors of Quaderni Rossi. ↩

-

Mattern, Shannon. “Maintenance and Care.” Places Journal, November 20, 2018. https://doi.org/10.22269/181120. ↩

-

François de Lerrard, Thierry Sadran, and Jean Maurice Balay, “Removable Urban Pavements: An Innovative, Sustainable Technology,” 5. ↩